Opera buffa in two acts (1816)

Libretto by Cesare Sterbini

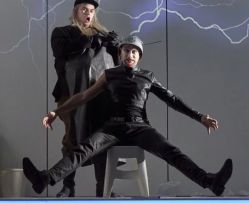

New production of Theater an der Wien at Kammeroper

New Premiere date:

Friday, 11 March 2022, 7 pm until 9.50 pm (intermission: 8.30 pm)

Performances:

13 | 26 | 29 | 31 March and 2 April 2022, 7 pm

Introduction matinée:

Sunday, 6 March 2022, 11 am

In Italian with German surtitles

Cast

Synopsis

Doctor Bartolo wishes to marry his ward Rosina whom he is keeping like a prisoner. He has his eye on her fortune. But Count Almaviva is also on the scene and in love with Rosina. He serenades her under the name of Lindoro. To get closer to her he allies himself with Figaro, a barber who goes in and out of Bartolo’s house at will. Rosina sees the good-looking Lindoro as the only means of escape from her guardian’s tyranny. In the meantime, Bartolo has learned that the notorious Count Almaviva is in Seville and apparently pursuing his Rosina. His friend, the music teacher Basilio, advises him to discredit the Count to Rosina to be on the safe side. However, Bartolo thinks it better to marry Rosina straightaway. Figaro warns Rosina and confirms that Lindoro loves her. Almaviva carries out his plan and, now disguised as a soldier, demands to be taken in by Bartolo, but his behaviour is so peculiar that he is nearly arrested and the plan fails. Next morning he again tries to gain admission to Bartolo’s house. This time he pretends to be one of Basilio’s pupils who has been sent as a stand-in teacher for Rosina because Basilio is allegedly ill. Bartolo is suspicious and never lets the two of them out of his sight. The lovers barely have time to devise a plan of escape before Basilio unexpectedly appears. He only calms down when Almaviva gives him a bag full of money. When Bartolo learns from Basilio some time later what is really going on he instructs the music teacher to fetch a notary without delay. He spitefully shows Rosina the letter she wrote to Lindoro earlier, saying it was given to him by Count Almaviva and that Lindoro is nothing more than the lecherous Count’s henchman. Rosina feels deceived and betrayed. When the Count and Figaro climb in with the aid of a ladder she initially refuses to let herself be abducted for the Count by the traitor Lindoro. But when she is assured that Lindoro and Almaviva are one and the same person she joyfully agrees to the marriage, to be performed by the notary who has been sent for. Bartolo, arriving too late, is left empty-handed and is forced to accept that all his efforts were nothing more than a useless precaution.

Gioachino Rossini’sIl barbiere di Siviglia is regarded as the epitome of opera buffa. The subject matter, the musical forms, the plot and the characters are all paradigms of the genre. Added to this is music of “exuberant animality”, as Friedrich Nietzsche put it, which makes for a masterpiece whose popularity remains unbroken today. Even Beethoven, who despised the Rossini frenzy in Vienna in the 1820s, could not help but express his admiration for this sparkling opera buffa. All this notwithstanding, the premiere on 20 February 1816 at the Teatro Argentino in Rome was a flop and is one of the most popularly cited scandals in the history of opera. Supporters of the composer Giovanni Paisiello, angered by the fact that Rossini had dared to set the subject matter, the first part of Beaumarchais’ Figaro trilogy, again after their favourite had done so, hissed and jeered after every number. However, nothing could stop the popularity of Rossini’s Barbiere from spreading all over the world. That said, the history of the work’s reception shows that the plot’s cunning ambiguity has been progressively diluted, with the provocative message of this comic opera unfortunately being often reduced to cheap farce. Rossini was one of the first to recognise the portents of a new age: the industrial revolution and capitalism were taking shape, and the composer exposed their dangerous folly on the stage as a warning for all to see. Is it not so that all the titular hero’s ingenious plans are solely a result of the stimulating effect of money? Bartolo is only interested in Rosina’s fortune, and the scheming Basilio is bursting with fantasies of power and destruction. Count Almaviva, on the other hand, is the prototype of a man from the wealthy upper classes who can turn everything to his advantage with privileges and pecuniary bribes. And is not Rosina in truth cold and calculating, always ready with a (white) lie? Stendhal said early on of her coloraturas that it was impossible to imagine anything colder. So Rossini’s masterpiece, which shows what happened before the events in that earlier stroke of genius, Mozart’s equally socially astute Le nozze di Figaro, is not just one of the most successful works in the opera literature: Il barbiere di Siviglia is more topical than ever.

About the opera

Gioachino Rossini’sIl barbiere di Siviglia is regarded as the epitome of opera buffa. The subject matter, the musical forms, the plot and the characters are all paradigms of the genre. Added to this is music of “exuberant animality”, as Friedrich Nietzsche put it, which makes for a masterpiece whose popularity remains unbroken today. Even Beethoven, who despised the Rossini frenzy in Vienna in the 1820s, could not help but express his admiration for this sparkling opera buffa. All this notwithstanding, the premiere on 20 February 1816 at the Teatro Argentino in Rome was a flop and is one of the most popularly cited scandals in the history of opera. Supporters of the composer Giovanni Paisiello, angered by the fact that Rossini had dared to set the subject matter, the first part of Beaumarchais’ Figaro trilogy, again after their favourite had done so, hissed and jeered after every number. However, nothing could stop the popularity of Rossini’s Barbiere from spreading all over the world. That said, the history of the work’s reception shows that the plot’s cunning ambiguity has been progressively diluted, with the provocative message of this comic opera unfortunately being often reduced to cheap farce. Rossini was one of the first to recognise the portents of a new age: the industrial revolution and capitalism were taking shape, and the composer exposed their dangerous folly on the stage as a warning for all to see. Is it not so that all the titular hero’s ingenious plans are solely a result of the stimulating effect of money? Bartolo is only interested in Rosina’s fortune, and the scheming Basilio is bursting with fantasies of power and destruction. Count Almaviva, on the other hand, is the prototype of a man from the wealthy upper classes who can turn everything to his advantage with privileges and pecuniary bribes. And is not Rosina in truth cold and calculating, always ready with a (white) lie? Stendhal said early on of her coloraturas that it was impossible to imagine anything colder. So Rossini’s masterpiece, which shows what happened before the events in that earlier stroke of genius, Mozart’s equally socially astute Le nozze di Figaro, is not just one of the most successful works in the opera literature: Il barbiere di Siviglia is more topical than ever.